There are surprisingly few original takes of the dive watch formula, and that is largely by design. The genre as we know it today found its footing in the mid 1950s alongside a burgeoning recreational diving subculture, with watches from the likes of Rolex, Doxa, Blancpain, and others casting a die that remains relevant today. While there is no shortage of unique concepts that can be found in the micro or independent brand space, the tentpole Swiss brands rarely venture off the beaten path thanks to a prevailing wisdom of ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’. And then, there’s the IWC Aquatimer, a watch that seems content living in the shadows. It wasn’t always this way, though, and the collection has a rich history with many bright spots, none more so than the reference 3536 hailing from IWC’s short lived GST collection of the late 1990s.

Rewinding back to 1997, just a few years prior to joining the Richemont family in 2000 (alongside A. Lange & Söhne and Jaeger-LeCoultre), IWC debuted the GST collection of watches. The concept here was to place existing sport watch designs into a new integrated case and bracelet structure featuring the use of Gold, Steel, and Titanium (or GST). This collection was strangely progressive even for the time, and the move itself feels almost unthinkable in today’s climate, but it was a necessity as IWC had just terminated their contract with Porsche Design. GST watches represented fertile testing grounds, and a broad range of complications made their way into the collection, from perpetual calendars and rattrapantes, to mechanical depth gauges.

In hindsight, it’s quite plain that the GST collection never came together with the cohesion and grace that it could have, but in some ways these watches were ahead of their time. The collection was an extension of Günter Blümlein’s influence on the brand, and a final breath of the Adolf Schindling era for the brand. These were sporty integrated bracelet tool watches that weren’t afraid to take some risks, and had they been given the opportunity to evolve and mature, I imagine that it would be a well embraced collection today. The underlying designs would of course carry on even after the GST was put to rest in 2003, as they were all based on existing watches, and IWC would go on to establish themselves as a luxury player in the space.

There is much more to say about this transitional period, and IWC’s full history around this era is quite fascinating given their propensity for exotic materials and complications. As stated in my review of the reference 3289 Ingenieur, there are many completions to IWC’s past, and the GST is another curious wrinkle to explore. There is one GST watch that I’d like to focus on here, and that is the titanium Aquatimer 2000 reference 3536.

As far as dive watches are concerned, the Aquatimer has always maintained a unique identity. First introduced in 1967 with the reference 812 with an internal rotating bezel, the Aquatimer had a strong, straightforward personality. Just a year later IWC followed up on this original design with a very different take on the collection that featured a cushion shaped case and colorful dial treatments that fell in line with many other divers of the era. This swap offers a foreshadow of a theme that would take hold at IWC over the coming generations, and that is adaptability at the expense of consistency.

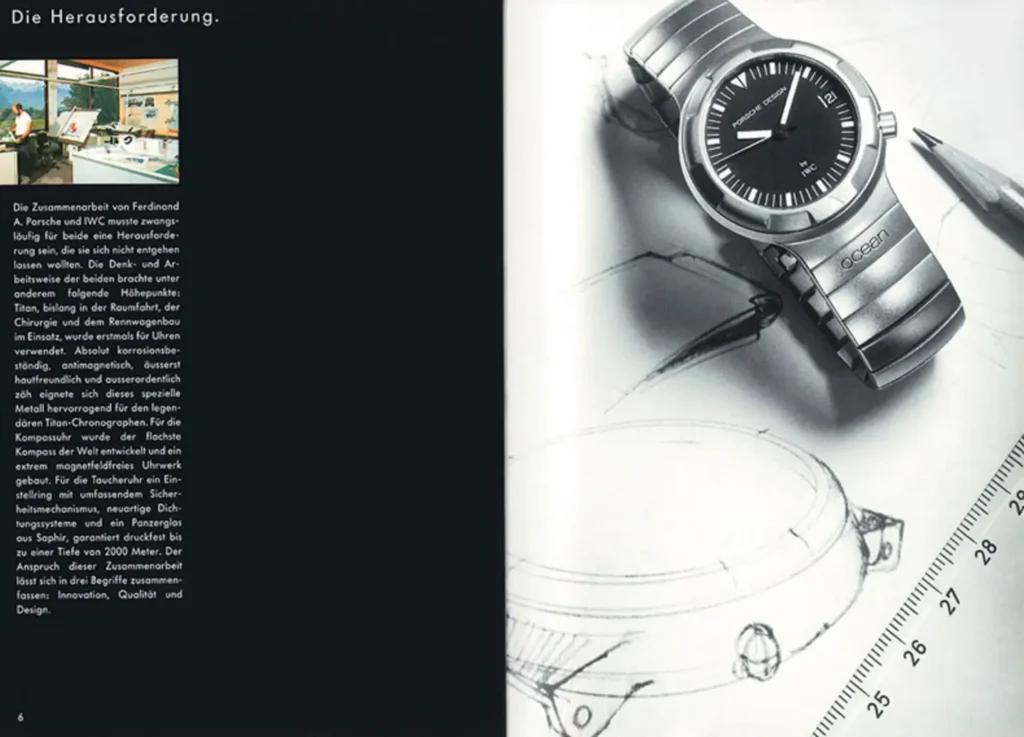

By the late ‘70s, IWC had developed a working relationship with Porsche Design, which would lead to some of the most distinctive watches to ever bear the brand’s name. The Ocean 2000 dive watch emerged in 1982 with a decidedly ‘80s vibe and a fully titanium case and integrated bracelet. This design language would evolve over the next decade before giving way to the GST collection at the conclusion of IWC’s partnership with Porsche Design. The GST brought the return of the Aquatimer name, and with it, a more extreme execution.

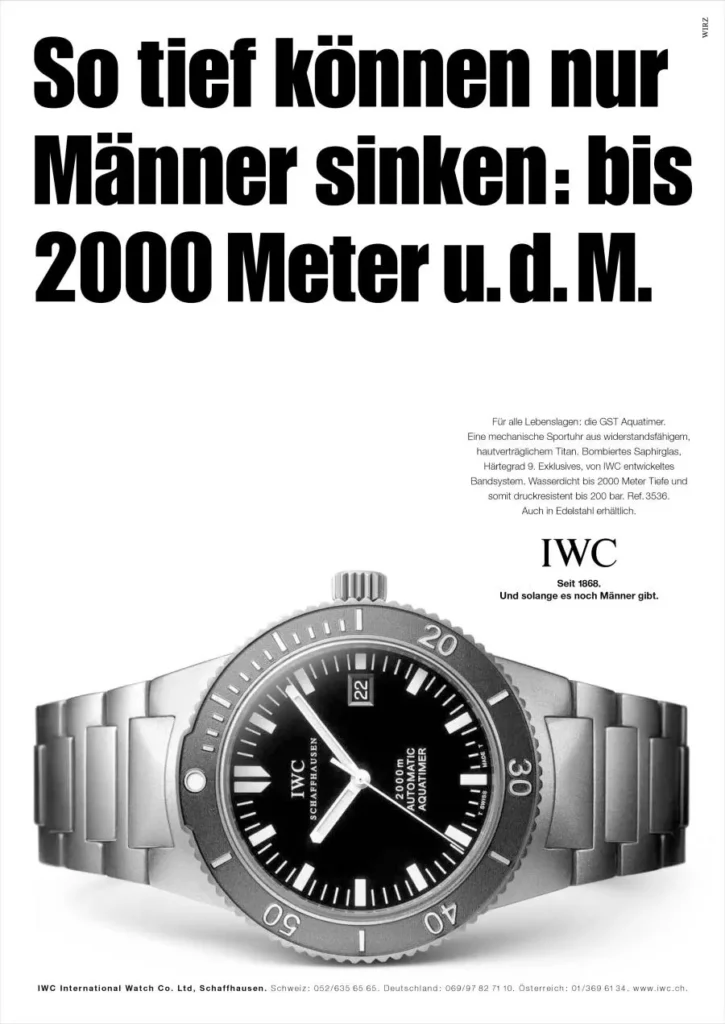

The GST Aquatimer 2000 reference 3536 was released with an impressive stat sheet, boasting a fully titanium case and integrated bracelet, measuring 42mm in diameter and 14.5mm in thickness, and a whopping 2000 meter depth rating. For comparison, the Rolex Sea-Dweller of the same era (ref. 16600) used a 40mm steel case and had to make do with a 1,220 meter depth rating. Though noticeably larger, the 3536 weighs about 25 grams less than the 16600 thanks to the use of titanium. Wearability is another discussion, but I’ll get to that shortly.

The GST Aquatimer has a strong visual identity thanks in large part to the shape of the case, bracelet, and bezel. The dial itself is once again, rather straightforward with lume applications marking each hour, and a set of pencil hands marking the time. There’s no big personality to speak of when it comes to the dial alone. Even the hour markers at the cardinal positions are the same size and shape as the rest of the hour markers. Only the double markings at 12 o’clock stand out as unique. It is a clinically clean representation of a diver, and it pushes the visual interest to literally every other element at work here. Thankfully, that’s exactly where the personality shines.

Framing the dial is a push-to-turn bezel that’s done in relief, with the markings rising out of a matte black base. A large notch at 12 o’clock breaks up the saw tooth texture, and allows for the wearer to use the bezel by feel alone (a slightly useless exercise given that you’d need to see what it’s being set against). The bezel assembly overhangs the case, and this is what sets the 42mm diameter measurement. As measured from the case itself, this is actually a 41mm watch. That said, this isn’t a small watch by any stretch, and it wears every bit of the diameter as you’d imagine.

A big factor in that is the case and integrated bracelet. The lugs immediately begin their taper toward a 20mm end link that connects to the case via male centerpiece, and this transition from case to lug is the defining visual feature of the watch. This is a highly angular design, with no real soft edges to speak of, and these flat surfaces make for an origami-like transition to the bracelet. It feels a bit unresolved when taken on its own, and the more you look at it the more unsettling it becomes. However, taken as a whole, it somehow works. It’s interesting and dynamic, and even the rough areas lend a huge amount to the overall personality of the watch.

So how does this all take shape on the wrist? Well, there’s plenty of personality there, as well. This is a fully titanium watch, but there’s still a generous amount of heft, as the watch weighs in at ~120 grams. It is a bit thick, however much of that is tucked into a belly that sits at the center of mass, so it does tuck into the wrist rather neatly. But overall, this is a watch with some presence, and that transition to the bracelet is noticeable as a part of the wearing experience. Compared to a watch like the aforementioned Sea-Dweller, there is a certain amount of drama with the IWC that, as much as it takes away from the daily wearability of the watch, adds to the overall experience of wearing it on occasion.

This brings me to my biggest gripe with the watch, which is, as you might have guessed, the oddly domed crystal. This crystal is only lightly shaped, but it has a lens distortion effect that picks up reflections in a layered manner. It’s a bit like looking through the bottom of a coke bottle, warping and distorting the world around you. In bright environments, it can be tricky to get a quick read on the time, but it’s not enough to take away from the experience as a whole.

I recently had lunch with IWC’s current Chief Design Officer, Christian Knoop, and he made an interesting point in regards to balancing the experience of wearing a watch with the ergonomics of the execution. He pondered that a great experience needn’t be ergonomic. Like driving a Ferrari may offer a uniquely compelling experience while at the same time being a horribly impractical daily driver. Thus, he argues, why worry ourselves about a few millimeters here or there if the experience is worth it?

His point is sound, and indeed a great reminder that a watch is more than a set of numbers on a page. I have a lot more to say about this topic, which will be saved for a discussion topic on an upcoming episode of the podcast.

The GST Aquatimer is most assuredly an interesting experience on the wrist. It’s bold, unexpected, and unapologetic. It is a testament to the kind of thinking taking place around sport watches as a whole in the mid to late ‘90s. Because of this, it’s a watch that feels strangely out of place in a modern context. In that regard, it’s a bit like the Zenith Rainbow Flyback, the Sinn EZM1, the Fortis OCC, and many others from the same general era. It’s dated, but in a way that makes you miss it.

On that note, IWC used an ETA 2892 automatic movement in these watches, which I find refreshing in an era when everything must be in-house or in-group in order to maximise value. With the 2892, you know exactly what you’re getting, and exactly where you can have it serviced over its lifespan. It’s a workhorse movement that’s well proven and easily fixable, which are qualities that add their own value, if you ask me. Sometimes, the best tool for the job isn’t the most glamorous. Its use here also lends to the overall tool-ish vibe of the watch (and to many watches of this era), as it never feels too precious.

The GST Aquatimer 2000 3536 is most certainly an experience that defines a particular era. It’s a bit strange and unwieldy, but it’s unique in character, and takes risks the likes of which we rarely see today. It is emblematic of the Aquatimer collection as a whole, and represents a path forward for a modern Aquatimer, that’s been somewhat frozen in time since releasing in 2014. Stepping back, the GST as a whole tapped into something that the enthusiast community is only recently coming around to appreciate.

IWC as a brand is in a very different place than they were in the late ‘90s. They make some truly compelling watches, and I think they are, broadly speaking, heading in the right direction. None of this should take away from what they were, and thankfully, examples of their recent past are more accessible than what you’ll find in their current catalog. GST watches aren’t uncommon on the pre-owned market, and there are many interesting references worth exploring. The Aquatimer 2000 feels like the most mature of the bunch, however, and that comes down to its simple charm, which allows for what I find to be the purest expression of the integrated bracelet design language.